In the expansive realm of the northern Pacific Ocean, a formidable oceanic ‘gyre’ orchestrates the convergence of numerous ocean currents, coalescing them into a singular domain—an area renowned as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP).

Long before plastic waste had invaded these waters, and remarkably, even in the face of its presence, the Northern Pacific Ocean gyre hosts an array of specially adapted marine organisms that gracefully meander through the aquatic expanse.

Consider, for instance, the enchanting violet snail; this creature crafts buoyant bubble rafts by delicately dipping its form into the surrounding air, entrapping individual bubbles one at a time. Each captured bubble is then cocooned in a glistening veil of mucus, affixed to its floating vessel—a remarkable display of nature’s ingenuity.

In recent times, scientists have meticulously chronicled an assorted multitude of life forms densely concentrated at the heart of the GPGP. Within this extraordinary environmental phenomenon, birthed by a staggering assemblage of 1.8 trillion plastic fragments, a unique tapestry of existence unfolds—a spectacle unparalleled on our planet.

In the year 2019, an intrepid swimmer named Benoît Lecomte embarked on a remarkable journey, traversing a distance of 389 miles across the expanse of the GPGP. Recognizing the significance of this endeavor, Lecomte enlisted the participation of scientists from Georgetown University, tasking them with documenting the hidden world of marine life that inhabits these waters.

The fruits of their labor have now been unveiled through the pages of the esteemed journal PLOS One. Their findings reveal a paradoxical truth: amidst the seas awash with trillions of plastic fragments, the core of the GPGP pulsates with a heightened concentration of wildlife. This phenomenon is not a consequence of the plastic invasion, but rather a testimony to the resilience of these seaborne voyagers, who, over millennia, have evolved to harness the dynamic currents and gyres of the ocean for their journeys.

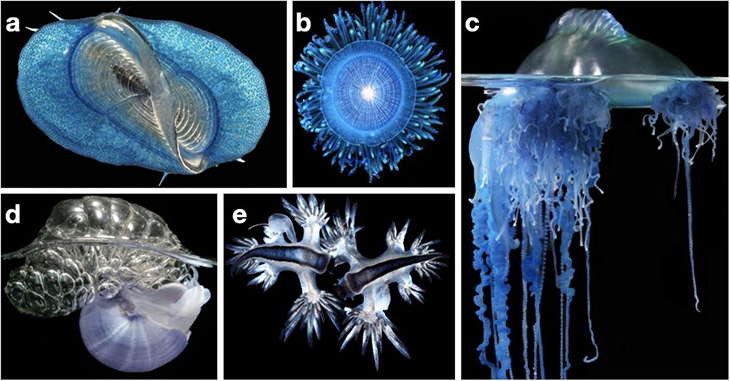

Within this mesmerizing realm, one encounters a vibrant assembly of beings. The violet snails, the blue button jellies, the by-the-wind sailor jellies, and the sea slugs known as blue sea dragons—all thrive in abundance. The blue sea dragons, in particular, exhibit a cunning strategy, preying upon the tentacles of formidable man o’ wars to fashion impromptu shields of protection.

Thus, the enigma of the GPGP unfolds—an extraordinary convergence of ecological tenacity and a testament to life’s adaptability, nestled within a realm defined by the inexorable forces of nature and the human footprint on the planet.

“We saw just massive amounts of life at the surface,” senior author Rebecca Helm, a marine biologist at Georgetown University, said when she spoke to National Geographic. “We’ve seen so many pictures of plastic from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, but we’ve never seen any pictures of life there.”

“These places that we’ve been calling garbage patches are really important ecosystems that we know very little about.”

The scientific term encompassing all the drifting marine organisms is “neuston,” with a significant portion exhibiting a blue upper surface and a white underside, which Helm and her research group theorize serves as a form of camouflage.

The majority of our youth might never have the opportunity to witness the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) firsthand. This is due to the current projection that it will undergo a thorough cleaning, even at the microplastic scale, within the next two decades.

What are your thoughts? Please comment below and share this news!

True Activist / Report a typo